Aside from love, one of the great emotions humans can experience is the thrill of discovery and achievement – being the first to reveal more of nature’s immutable laws governing the cosmos or doing something no one else has been able to do.  Some aspects of life inevitably go together – a coupling of cause-and-effect, if you will. Sometimes, we simply cannot have one thing without another. The claim that “there is a price to be paid for everything” seems a truism which ably illustrates that contention of coupled cause-and-effect. In that vein, man’s finest intellectual achievements or physical accomplishments materialize only after significant vested effort is expended. Our personal life experiences leave no doubt that hard work is a necessary, though not sufficient, prerequisite for great success…in any venue. We understand that. Not so obvious is the other price often associated with intellectual achievement and intellectual property, a price which is extracted after the fact – the tedious, ongoing, and costly effort required to establish and maintain the legal rights to the intellectual property behind any significant achievement.

Some aspects of life inevitably go together – a coupling of cause-and-effect, if you will. Sometimes, we simply cannot have one thing without another. The claim that “there is a price to be paid for everything” seems a truism which ably illustrates that contention of coupled cause-and-effect. In that vein, man’s finest intellectual achievements or physical accomplishments materialize only after significant vested effort is expended. Our personal life experiences leave no doubt that hard work is a necessary, though not sufficient, prerequisite for great success…in any venue. We understand that. Not so obvious is the other price often associated with intellectual achievement and intellectual property, a price which is extracted after the fact – the tedious, ongoing, and costly effort required to establish and maintain the legal rights to the intellectual property behind any significant achievement.

I call this second price to be paid for success “the indigestion of success” which is often so severe as to result literally in ulcers if not merely pervasive, never-ending discontent.

The “indigestion of success” begins with proving one’s priority of invention while establishing patent rights, and it continues seemingly forever while vigilantly protecting those rights against usurpers. The motivation to defend one’s intellectual property is typically financial, but, understandably, the battle becomes distinctly a matter of personal principle as we will see…and the consequences can be tragic. It is difficult to overstate the high price – both financially and emotionally – of defending intellectual property and priority, yet this surcharge on success is inevitably demanded of inventors, engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs. The list of such examples is varied and fascinating, stretching far back in recorded history. Gaileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, and Michael Faraday, three of the greatest physicists of all time were each affected by priority controversies during their careers – especially Newton, as we shall see. In the realms of engineering and business, Thomas Edison, Howard Armstrong (radio’s greatest inventor/engineer), Robert Noyce (of integrated circuit fame), and Steve Jobs of Apple Computer were all enveloped by priority controversies and patent battles. Even the Wright brothers, the well-documented founders of modern aviation paid a stiff price defending their marvelous invention, the controllable “flying machine.”

The Wright Brothers: Hard Work, Triumph, then Disillusionment

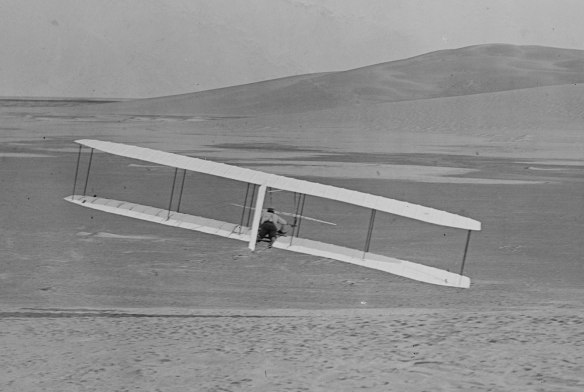

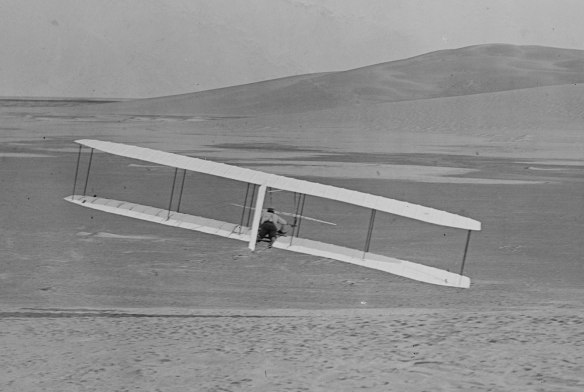

I just finished reading David McCullough’s new book, The Wright Brothers, which relates the incredible story of the two brothers from Dayton, Ohio – bicycle mechanics/salesmen who created the first true “flying machine”…in their spare time! McCullough is a consummate teller of true stories, but the story of these two men tests the line separating fact from fiction because their stunning success seemed so improbable. The truth is, the Wright Brothers “invented” and successfully flew the first full-sized, self-powered, controllable airplane – a staggering accomplishment for two young men with no formal technical credentials. Their ultimate success was rooted in a fascination at the prospect of manned flight coupled with a single-minded, driven determination to do whatever it takes to accomplish their dream of flying. The two brothers constitute the very best examples of self-made men… engineers and flyers, in their case. Their accomplishments are so thoroughly documented as to seem unassailable and safe from thieves who would steal in the courts of patent law, yet it was not quite that simple. It never is. Author McCullough paints a clear picture on his pages of just how technically challenging their task actually was. What also emerges is the sad turn of events their triumph became once the airplane was designed, tested, documented, and patented. Wilbur Wright, the brilliant engineering mind for whom no technical challenge seemed too large, died early in 1912 at the young age of forty-five years. The official cause of death was typhoid fever, but it seems Wilbur’s spirit was dying for quite some time before his body expired. In May of 1910, the brothers, who did all their own flying from the project’s onset in 1900, went up together in their Wright Flyer for the very first time – some seven years after Orville’s first flight at Kitty Hawk. Their disciplined methodology throughout the project dictated that, should there be an accident, at least one of them should survive to carry on the work. Their flight together that day seemed their tacit acknowledgement that they had completed their life’s dream; all that remained was to form and grow a profitable company which would carry on their work and insure a comfortable livelihood for the brothers and their immediate relatives.

I just finished reading David McCullough’s new book, The Wright Brothers, which relates the incredible story of the two brothers from Dayton, Ohio – bicycle mechanics/salesmen who created the first true “flying machine”…in their spare time! McCullough is a consummate teller of true stories, but the story of these two men tests the line separating fact from fiction because their stunning success seemed so improbable. The truth is, the Wright Brothers “invented” and successfully flew the first full-sized, self-powered, controllable airplane – a staggering accomplishment for two young men with no formal technical credentials. Their ultimate success was rooted in a fascination at the prospect of manned flight coupled with a single-minded, driven determination to do whatever it takes to accomplish their dream of flying. The two brothers constitute the very best examples of self-made men… engineers and flyers, in their case. Their accomplishments are so thoroughly documented as to seem unassailable and safe from thieves who would steal in the courts of patent law, yet it was not quite that simple. It never is. Author McCullough paints a clear picture on his pages of just how technically challenging their task actually was. What also emerges is the sad turn of events their triumph became once the airplane was designed, tested, documented, and patented. Wilbur Wright, the brilliant engineering mind for whom no technical challenge seemed too large, died early in 1912 at the young age of forty-five years. The official cause of death was typhoid fever, but it seems Wilbur’s spirit was dying for quite some time before his body expired. In May of 1910, the brothers, who did all their own flying from the project’s onset in 1900, went up together in their Wright Flyer for the very first time – some seven years after Orville’s first flight at Kitty Hawk. Their disciplined methodology throughout the project dictated that, should there be an accident, at least one of them should survive to carry on the work. Their flight together that day seemed their tacit acknowledgement that they had completed their life’s dream; all that remained was to form and grow a profitable company which would carry on their work and insure a comfortable livelihood for the brothers and their immediate relatives.

![WilburWright7[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/wilburwright71.jpg) By 1912, two years had passed since Wilbur Wright had last done what he truly loved to do: Piloting the Wright Flyer while perfecting its design. His weeks and months the past two years were spent on business trips to New York and Washington and in courtrooms defending the patent portfolio he and Orville had assembled as the backbone of their new Wright Company… for the manufacture of airplanes. In author McCullough’s account, Orville took note of Wilbur’s restless discontent with the tedium and exasperations of establishing their company, noting that after a day spent in offices dealing with business and patent matters, Wilbur would “come home white.”

By 1912, two years had passed since Wilbur Wright had last done what he truly loved to do: Piloting the Wright Flyer while perfecting its design. His weeks and months the past two years were spent on business trips to New York and Washington and in courtrooms defending the patent portfolio he and Orville had assembled as the backbone of their new Wright Company… for the manufacture of airplanes. In author McCullough’s account, Orville took note of Wilbur’s restless discontent with the tedium and exasperations of establishing their company, noting that after a day spent in offices dealing with business and patent matters, Wilbur would “come home white.”

Wilbur, himself, wrote of the patent entanglements: “When we think of what we might have accomplished if we had been able to devote this time to experiments, we feel very sad, but it is always easier to deal with things than with men, and no one can direct his life entirely as he would choose.”

Within several years of Wilbur’s death, Orville Wright had sold the Wright Company to others, preferring a peaceful, retiring life to one spent constantly battling corporate demons and those who would usurp the brothers’ past and future accomplishments. His mission for the remainder of his long life: To represent his brother while defending the less materialistic aspects of the Wright brothers’ legacy. I believe I would have done precisely the same, were I in his shoes. Other notable, historical figures in similar circumstances made sadly different decisions when faced with the indigestion of success and the never-ending need to protect intellectual property. The two examples that follow vividly illustrate just how bad these matters of priority and intellectual property can become, especially for the most-principled of participants.

Edwin Howard Armstrong: Radio’s Greatest Inventor/Engineer and Tragic Victim of His Own Success and the Patent System

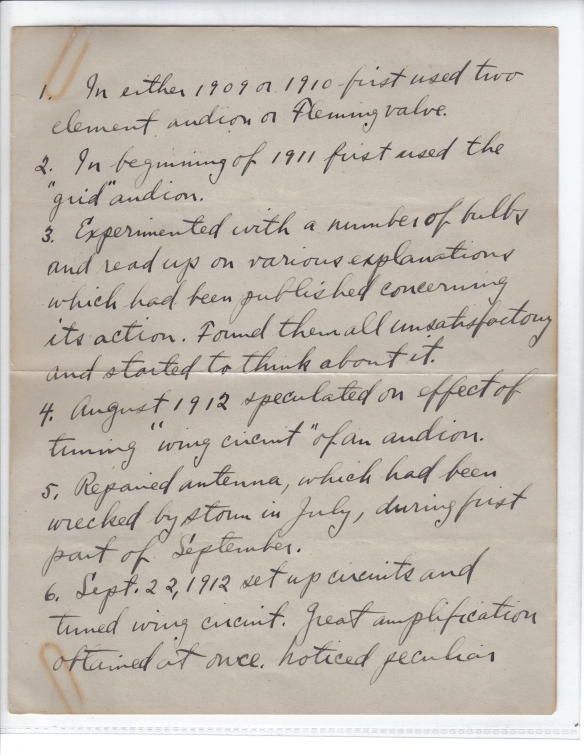

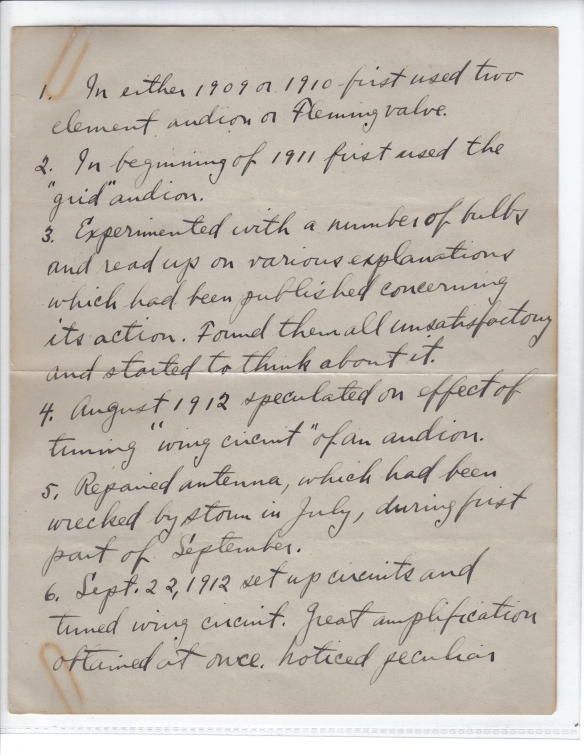

For radio and electrical engineers who know the history, Edwin Howard Armstrong is the tragic hero of early “wireless” and a victim of the radio empire which he helped to create. Howard Armstrong was the quintessential radio engineer’s engineer – bright, motivated, creative…and stubbornly persistent. He exuded personal integrity. The very qualities which made him the greatest inventor/engineer in the history of radio, led to his downfall and suicide in 1954. Howard Armstrong surfaced in 1912 as a senior electrical engineering major at Columbia University with an obsessive interest in the infant science of “wireless” radio. He was a fine student with a probing, independent mind that suffered no fools. In 1912, while living at home in nearby Yonkers, New York, and commuting daily to Columbia on an Indian-brand motorcycle, he invented a way to greatly increase signal amplification using a single De Forest Audion vacuum tube by feeding part of the tube’s marginally amplified output back to the input of the device where it was amplified over and over again. This technique is now known in the trade as “regeneration,” or positive feedback. Along the way, young Armstrong had made great strides in understanding the technology behind Lee De Forest’s recent invention of the Audion tube, insights far beyond those De Forest himself had offered. While tinkering with the idea of signal regeneration in his bedroom laboratory early on the morning of September 22, 1912, he achieved much greater signal amplification from the Audion than was possible without using regeneration. The entire household was abruptly awakened by young Armstrong’s unrestrained excitement over his discovery, and an important discovery it was for the infant science of “wireless radio.” Regeneration was patented by Armstrong in 1913/14 and was used, under license from him, in countless radios during the early years when radio sets with more than one tube were very expensive to produce, due to the high cost of tubes.

Armstrong’s 1914 patent on the regenerative receiving circuit – one of the foundations of early wireless radio and a gateway to efficient tube-based radio transmitters, as well.

Armstrong’s 1914 patent on the regenerative receiving circuit – one of the foundations of early wireless radio and a gateway to efficient tube-based radio transmitters, as well.  Armstrong’s historic, handwritten chronological account of inventing the regenerative circuit – page one of six; likely written around 1920 to serve as evidence in the litigation with De Forest over Armstrong’s regeneration patent. Note the Sept. 22, 1912 date of his triumph (near the bottom).

Armstrong’s historic, handwritten chronological account of inventing the regenerative circuit – page one of six; likely written around 1920 to serve as evidence in the litigation with De Forest over Armstrong’s regeneration patent. Note the Sept. 22, 1912 date of his triumph (near the bottom).

In 1914, Lee De Forest stepped forward to challenge Armstrong in court over Armstrong’s patent, claiming that he, De Forest, was the legitimate inventor of regeneration. The litigation in the court system over regeneration went back and forth, lasting twenty years and finally ending up in the United States Supreme Court. Shockingly, De Forest was handed the final decision by the court, but the substantial body of radio engineers across the nation in 1934, who were well aware of the “radio art” and its history, were not buying De Forest’s claim. They fully supported Armstrong as the legitimate inventor – the same view held today. The twenty-year patent litigation battle over regeneration was the longest in U.S. patent court history. Unfortunately, that was only the beginning of Armstrong’s troubles with the patent courts and those who would take advantage of his work.

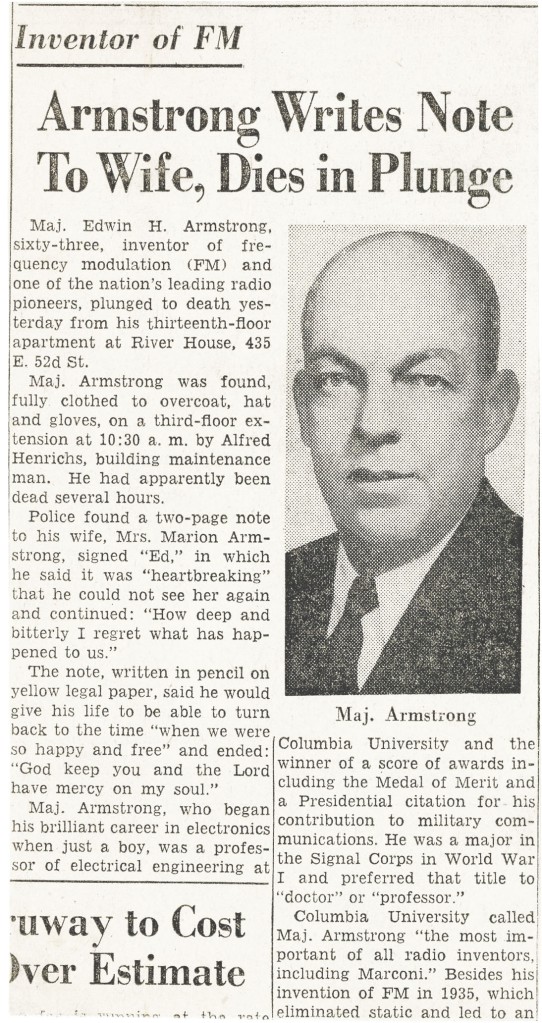

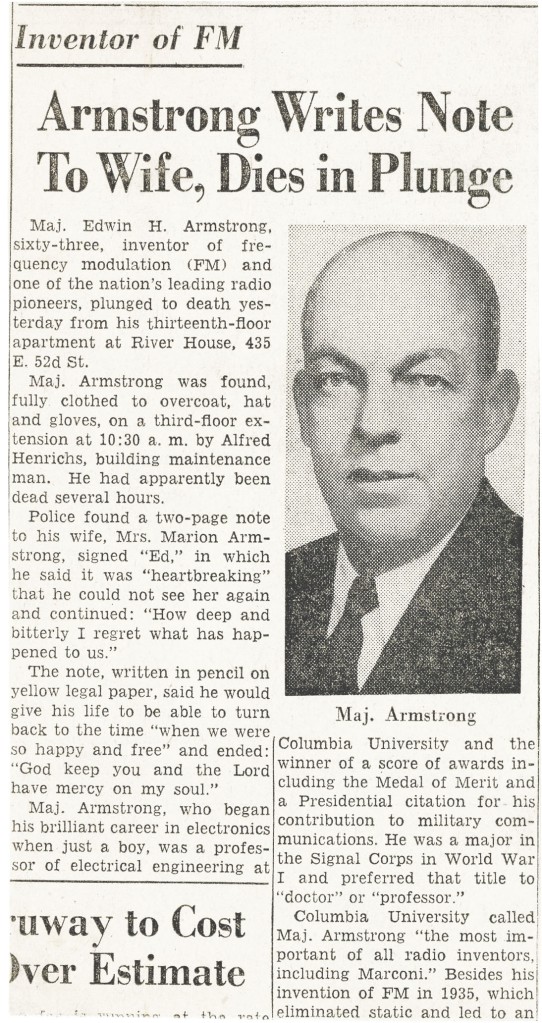

The Tragedy of Edwin Howard Armstrong

Howard Armstrong was one of the last, great, lone-inventor/engineers. He was long affiliated with his alma-mater, Columbia University, and had extensive business/patent dealings with giant corporations, such as RCA and Philco, which drew their life-blood from his inventions and the industry which he helped to create. By licensing his many important patents to these corporations, Armstrong became a very wealthy man. At one time, he was the largest stockholder in the giant RCA Corporation. Despite such wide-spread affiliations, he was, by temperament, an independent thinker in the lone-inventor mold. As radio entered the late nineteen thirties, men-of-action like Armstrong were becoming obsolete, increasingly overrun by corporate bureaucracies and their in-house armies of engineers. Radio was now out of the hands of the lone-inventor, becoming the exclusive domain of the moneyed corporations with influence at the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) in Washington. Armstrong increasingly found himself defending his legitimate patent rights against large corporations which were treading on those rights, battling their great financial resources and their legions of corporate lawyers. As he continued to lose rightful patent royalties to corporate violations of his patents, he stubbornly fought back fueled by his personal principles of fair play, all the while dissipating his once-great financial security to fund the necessary lawyer’s fees. Armstrong was a man of principled integrity; he could have capitulated, retreated, retired comfortably, and lived out his life, but he chose to fight.

Ultimately, those ceaseless legal battles wore him down, bankrupted him, and destroyed his long marriage. On May 5, 1954, he stepped from his New York apartment window to his death thirteen stories below. In an ironic sense, he fell victim to the industry and the changing times he helped to create. He also was victimized by the very qualities which made him great: Intellectual independence, principled integrity, and the stubborn will to persevere. There are many lessons to be learned from Howard Armstrong’s life-story. The lone crusader was crushed by the corporate “Goliaths” he helped create. Final postscript: After Armstrong’s death, his estranged wife, Marion, took up her husband’s ongoing patent battles with the Goliaths of the radio industry. She eventually prevailed in every single case!

Ultimately, those ceaseless legal battles wore him down, bankrupted him, and destroyed his long marriage. On May 5, 1954, he stepped from his New York apartment window to his death thirteen stories below. In an ironic sense, he fell victim to the industry and the changing times he helped to create. He also was victimized by the very qualities which made him great: Intellectual independence, principled integrity, and the stubborn will to persevere. There are many lessons to be learned from Howard Armstrong’s life-story. The lone crusader was crushed by the corporate “Goliaths” he helped create. Final postscript: After Armstrong’s death, his estranged wife, Marion, took up her husband’s ongoing patent battles with the Goliaths of the radio industry. She eventually prevailed in every single case!

Inventor of the Calculus: Isaac Newton or the German Mathematician, Gottfried Leibniz?

History’s most ardent defender of his intellectual property also happened to be the greatest scientist/mathematician of all time, Sir Isaac Newton. As vindictive as he was brilliant, Newton waged one of history’s most vicious priority battles with Gottfried Leibniz over credit for the development of the calculus, that ubiquitous, indispensable mathematical tool of the engineer and scientist. Newton formulated its fundamentals in 1665/66, the famous “miracle year” spent at his mother’s homestead in isolation from the great plague which swept through England at the time. ![GodfreyKneller-IsaacNewton-1689[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/godfreykneller-isaacnewton-16891.jpg) Newton’s peerless scientific self-discipline tended to completely desert him when challenged by others on matters of intellectual priority which he felt belonged to him. Leibniz and Robert Hooke were two men who famously felt the full force of Newton’s rage in such matters. For Newton and his circumstances, there was no real money at stake – only prestige and ego, and Newton’s ego was well-developed… and sensitive. Today, both Newton and Leibniz are credited with independently developing the calculus – essentially true, although it appears certain that Leibniz had unauthorized access to some of Newton’s early personal papers on the subject. In that sense, Newton is regarded as the “primary” developer of calculus. Leibniz never quite recovered from the savage and telling effects of Newton’s vindictiveness which was well publicized in scientific circles and which reduced the great Newton to unprincipled deceits in his efforts to discredit his rival. In Newton’s mind, much more was at stake than mere money: For him, personal satisfaction and the ego-satisfying prospect of scientific immortality were far more important motivators. In his defense, one could argue that, for Newton, the long-term stakes riding on his efforts to receive due credit for his brilliance were much higher than most. Nevertheless, when all was said and done, Newton’s personal reputation suffered significantly even if his scientific reputation remained unsullied over the dispute with Leibniz.

Newton’s peerless scientific self-discipline tended to completely desert him when challenged by others on matters of intellectual priority which he felt belonged to him. Leibniz and Robert Hooke were two men who famously felt the full force of Newton’s rage in such matters. For Newton and his circumstances, there was no real money at stake – only prestige and ego, and Newton’s ego was well-developed… and sensitive. Today, both Newton and Leibniz are credited with independently developing the calculus – essentially true, although it appears certain that Leibniz had unauthorized access to some of Newton’s early personal papers on the subject. In that sense, Newton is regarded as the “primary” developer of calculus. Leibniz never quite recovered from the savage and telling effects of Newton’s vindictiveness which was well publicized in scientific circles and which reduced the great Newton to unprincipled deceits in his efforts to discredit his rival. In Newton’s mind, much more was at stake than mere money: For him, personal satisfaction and the ego-satisfying prospect of scientific immortality were far more important motivators. In his defense, one could argue that, for Newton, the long-term stakes riding on his efforts to receive due credit for his brilliance were much higher than most. Nevertheless, when all was said and done, Newton’s personal reputation suffered significantly even if his scientific reputation remained unsullied over the dispute with Leibniz.

What Would You Do?

![Milton_Wright_1889[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/milton_wright_18891.jpg) If you were ever in the position of enjoying a significant personal success that had already conferred substantial wealth upon you, yet huge wealth beckons you or whoever else takes the enterprise still further – what would you do? Like Orville did, I would have heeded Bishop Milton Wright’s early admonition to his children (paraphrased here) that greed is bad and leads to grief; be content with sufficient money to sustain a comfortable life and require nothing more beyond that than the normal pleasures of life and living. The Bishop also warned against temper and ego. The Bishop was a very wise man; the brothers received some very informed guidance.

If you were ever in the position of enjoying a significant personal success that had already conferred substantial wealth upon you, yet huge wealth beckons you or whoever else takes the enterprise still further – what would you do? Like Orville did, I would have heeded Bishop Milton Wright’s early admonition to his children (paraphrased here) that greed is bad and leads to grief; be content with sufficient money to sustain a comfortable life and require nothing more beyond that than the normal pleasures of life and living. The Bishop also warned against temper and ego. The Bishop was a very wise man; the brothers received some very informed guidance.

“If I were giving a young man advice as to how he might succeed in life, I would say to him, pick out a good father and mother, and begin life in Ohio.”

– Wilbur Wright

Click here to get to last week’s post, The Brothers Wright had “The Right Stuff”

![WilburWright7[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/wilburwright71.jpg)

Armstrong’s 1914 patent on the regenerative receiving circuit – one of the foundations of early wireless radio and a gateway to efficient tube-based radio transmitters, as well.

Armstrong’s 1914 patent on the regenerative receiving circuit – one of the foundations of early wireless radio and a gateway to efficient tube-based radio transmitters, as well.

![GodfreyKneller-IsaacNewton-1689[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/godfreykneller-isaacnewton-16891.jpg)

![Milton_Wright_1889[1]](https://reasonandreflection.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/milton_wright_18891.jpg)